Part of Putting the “You” in CPU: a rabbit hole into how your computer runs programs.

Chapter 2:

Slice Dat Time

Edit on GitHub

Let’s say you’re building an operating system and you want users to be able to run multiple programs at once. You don’t have a fancy multi-core processor though, so your CPU can only run one instruction at a time!

Luckily, you’re a very smart OS developer. You figure out that you can fake parallelism by letting processes take turns on the CPU. If you cycle through the processes and run a couple instructions from each one, they can all be responsive without any single process hogging the CPU.

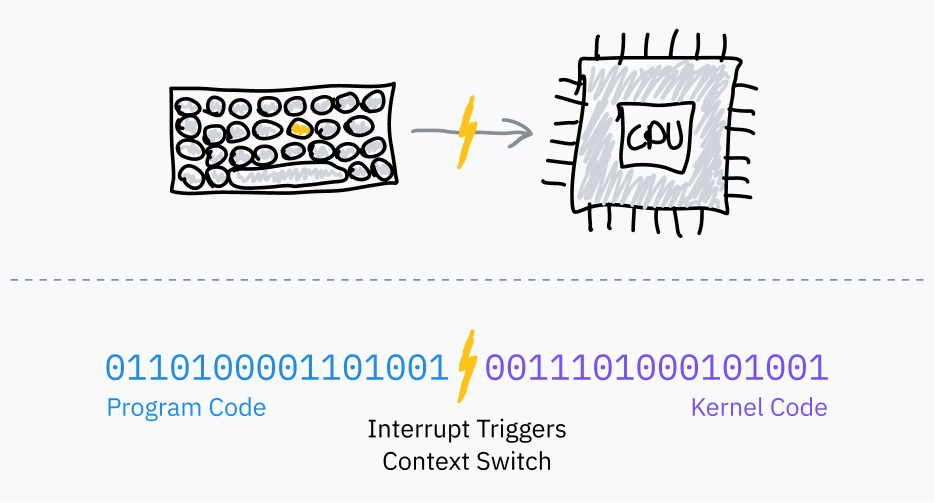

But how do you take control back from program code to switch processes? After a bit of research, you discover that most computers come with timer chips. You can program a timer chip to trigger a switch to an OS interrupt handler after a certain amount of time passes.

Hardware Interrupts

Earlier, we talked about how software interrupts are used to hand control from a userland program to the OS. These are called “software” interrupts because they’re voluntarily triggered by a program — machine code executed by the processor in the normal fetch-execute cycle tells it to switch control to the kernel.

OS schedulers use timer chips like PITs to trigger hardware interrupts for multitasking:

- Before jumping to program code, the OS sets the timer chip to trigger an interrupt after some period of time.

- The OS switches to user mode and jumps to the next instruction of the program.

- When the timer elapses, it triggers a hardware interrupt to switch to kernel mode and jump to OS code.

- The OS can now save where the program left off, load a different program, and repeat the process.

This is called preemptive multitasking; the interruption of a process is called preemption. If you’re, say, reading this article on a browser and listening to music on the same machine, your very own computer is probably following this exact cycle thousands of times a second.

Timeslice Calculation

A timeslice is the duration an OS scheduler allows a process to run before preempting it. The simplest way to pick timeslices is to give every process the same timeslice, perhaps in the 10 ms range, and cycle through tasks in order. This is called fixed timeslice round-robin scheduling.

Aside: fun jargon facts!

Did you know that timeslices are often called “quantums?” Now you do, and you can impress all your tech friends. I think I deserve heaps of praise for not saying quantum in every other sentence in this article.

Speaking of timeslice jargon, Linux kernel devs use the jiffy time unit to count fixed frequency timer ticks. Among other things, jiffies are used for measuring the lengths of timeslices. Linux’s jiffy frequency is typically 1000 Hz but can be configured when compiling the kernel.

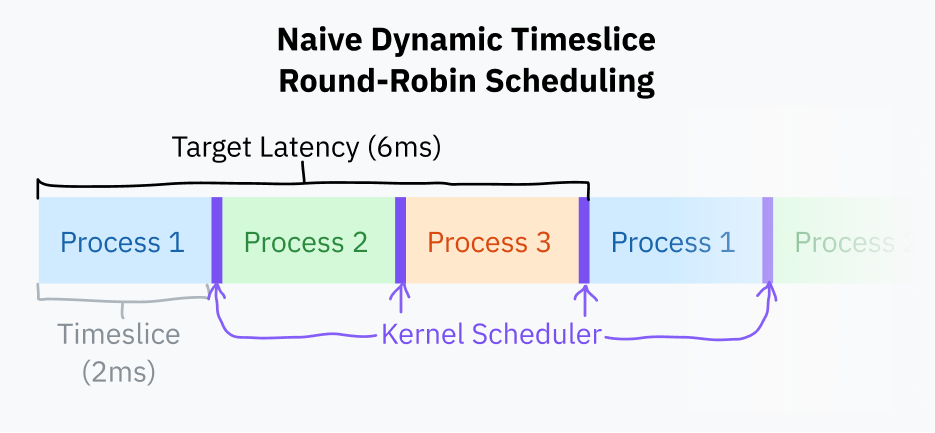

A slight improvement to fixed timeslice scheduling is to pick a target latency — the ideal longest time for a process to respond. The target latency is the time it takes for a process to resume execution after being preempted, assuming a reasonable number of processes. This is pretty hard to visualize! Don’t worry, a diagram is coming soon.

Timeslices are calculated by dividing the target latency by the total number of tasks; this is better than fixed timeslice scheduling because it eliminates wasteful task switching with fewer processes. With a target latency of 15 ms and 10 processes, each process would get 15/10 or 1.5 ms to run. With only 3 processes, each process gets a longer 5 ms timeslice while still hitting the target latency.

Process switching is computationally expensive because it requires saving the entire state of the current program and restoring a different one. Past a certain point, too small a timeslice can result in performance problems with processes switching too rapidly. It’s common to give the timeslice duration a lower bound (minimum granularity). This does mean that the target latency is exceeded when there are enough processes for the minimum granularity to take effect.

At the time of writing this article, Linux’s scheduler uses a target latency of 6 ms and a minimum granularity of 0.75 ms.

Round-robin scheduling with this basic timeslice calculation is close to what most computers do nowadays. It’s still a bit naive; most operating systems tend to have more complex schedulers which take process priorities and deadlines into account. Since 2007, Linux has used a scheduler called Completely Fair Scheduler. CFS does a bunch of very fancy computer science things to prioritize tasks and divvy up CPU time.

Every time the OS preempts a process it needs to load the new program’s saved execution context, including its memory environment. This is accomplished by telling the CPU to use a page table, a mapping from “virtual” to physical addresses. This is also how the OS prevents programs from accessing each other’s memory; we’ll go down this rabbit hole in chapters 5 and 6 of this article.

Note #1: Kernel Preemptability

So far, we’ve been only talking about the preemption and scheduling of userland processes. Kernel code might make programs feel laggy if it took too long handling a syscall or executing driver code.

Modern kernels, including Linux, are preemptive kernels. This means they’re programmed in a way that allows kernel code itself to be interrupted and scheduled just like userland processes.

This isn’t very important to know about unless you’re writing a kernel or something, but basically every article I’ve read has mentioned it so I thought I would too! Extra knowledge is rarely a bad thing.

Note #2: A History Lesson

Ancient operating systems, including classic Mac OS and versions of Windows long before NT, used a predecessor to preemptive multitasking. Rather than the OS deciding when to preempt programs, the programs themselves would choose to yield to the OS. They would trigger a software interrupt to say, “hey, you can let another program run now.” These explicit yields were the only way for the OS to regain control and switch to the next scheduled process.

This is called cooperative multitasking. It has a couple major flaws: malicious or just poorly designed programs can easily freeze the entire operating system, and it’s nigh impossible to ensure temporal consistency for realtime/time-sensitive tasks. For these reasons, the tech world switched to preemptive multitasking a long time ago and never looked back.

Continue to Chapter 3: How to Run a Program